January 2025

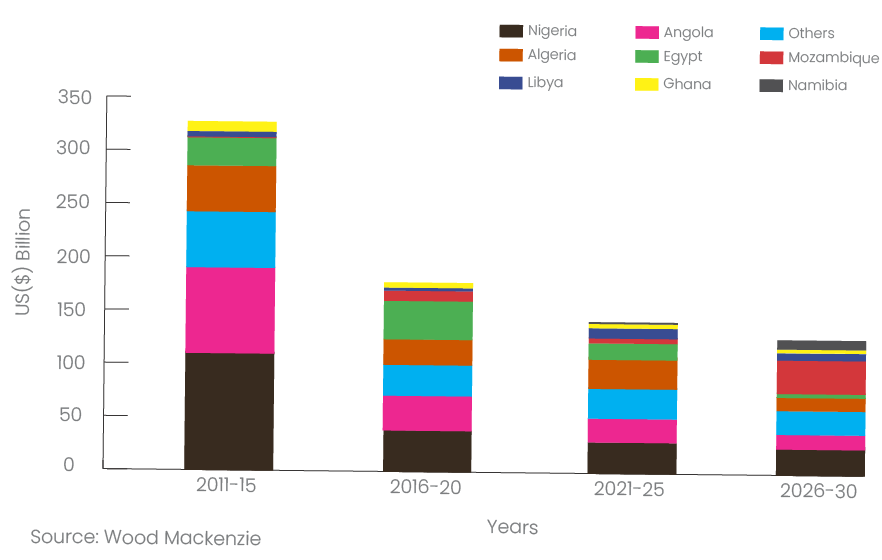

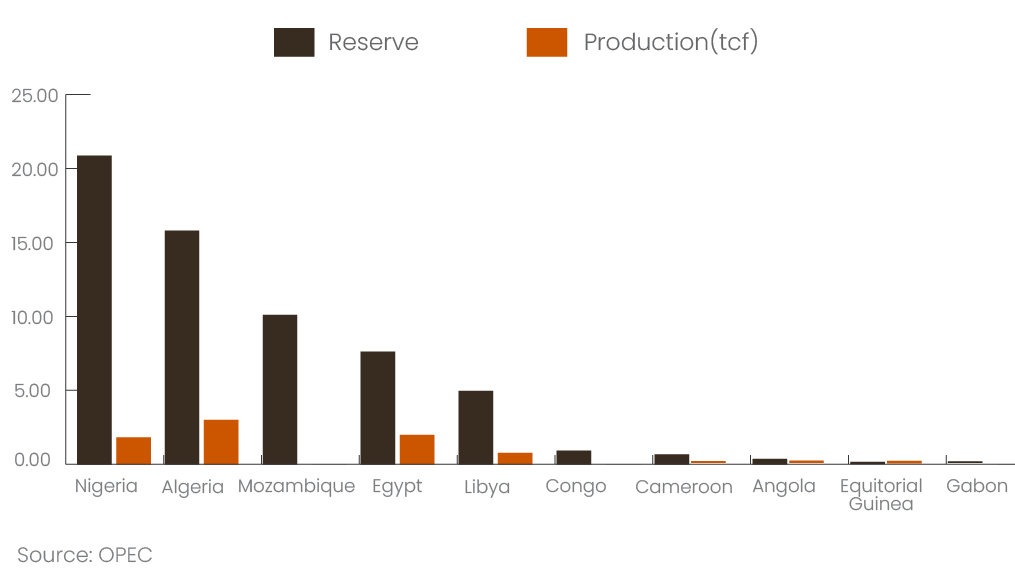

Africa boasts 800 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of natural gas reserves, attracting $245 billion in planned investments for LNG terminals, gas pipelines, and power stations. However, many of these projects face significant challenges, including inefficiencies, lack of capital, policy gaps, insecurity, and more, putting their realization at risk.

Fig. 1 – Gas Investments in Africa

Challenges the African gas industry face extend beyond supply to demand. Industries such as agriculture (fertilizers) and manufacturing, which typically drive gas demand, are underdeveloped due to Africa’s slow-paced industrialization. In 2022, Africa’s natural gas demand was 5.8 tcf, and rose by 6.9% in 2023. This growth pales in comparison to industrialized countries like the U.S., where demand is projected to grow by 54% by 2025. As a result, Africa derives most of its value from natural gas through exports, with 43% of the gas produced in 2023 exported, primarily to Europe due to its proximity.

Africa’s gas industry is majorly export-oriented.

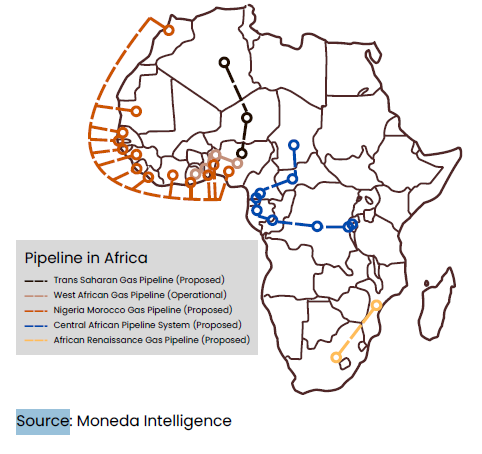

This export focus is reflected in infrastructure planning, where 75% of Africa’s 12 major planned gas projects prioritize exports rather than meeting domestic needs. To buttress this further, Major project like Nigeria’s NLNG plant, Algeria’s Medgaz pipeline, and Mozambique’s Coral Sul FLNG facility with a total of about 1.4 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of gas annually are predominantly export infrastructure.

Fig. 2 – Proposed and Operational Pipelines in Africa

While exports are good for government revenue, in this case, it has exposed African countries to energy security issues. As investments continue to isolate the domestic market, the continent remains dependent on imports despite its immense gas production potential and relatively low demand/consumption.

Fig. 3 – Natural Gas Reserves and Production by Country (OPEC members), 2022

In 2023, Nigeria produced 2.49 tcf of gas – enough to cater to the consumption of the whole of West Africa 2 times over yet 57.14% of its LPG consumption that year were imported. However, there is a growing shift toward more inclusive projects, such as the Trans-Saharan and Nigeria-Morocco pipelines, which aim to integrate domestic, regional, and export markets. Despite this progress, the industry faces a persistent lack of investment, with the combined cost of these pipelines exceeding $38 billion – nearly equivalent to the annual investment average for the entire sector over the past 15 years.

Government involvement is a blessing and a curse

Government-owned companies play a dominant role in natural gas developments across Africa, particularly in mature markets like Nigeria, Algeria, and Angola, where they control significant stakes in major projects.

While government involvement is seen as a means to safeguard national interests, it has often deterred investments due to delays, inefficiencies, and disputes. This contrast is evident in Nigeria, where state-led projects like the Ogidigben Gas Project (inaugurated in 2015) remain stalled due to federal disputes, while privately-led ventures like Seplat’s ANOH Gas Processing Plant secured financing in 2019 and completed in 2023. Similar patterns of delays and investor withdrawal plagued the Brass LNG and Olokola LNG projects, proposed in 2003 and 2005 respectively.

In countries like Mozambique and Tanzania where IOCs drive developments while government-owned entities take supporting roles, effective project development can be observed. For instance, the Coral Sul FLNG project in Mozambique driven by Eni was completed in 38 months which remains a record for the continent.

Financiers are becoming allergic to African gas projects.

Natural gas projects are facing challenges in securing funding due to the growing reluctance of global financiers to support fossil fuel projects. Major lenders like Barclays, HSBC, and BNP Paribas are tightening their lending policies for oil and gas companies, choosing instead to redirect funding towards renewable energy initiatives, with a collective target of $1 trillion in sustainable financing by 2030 to combat climate change.

Africa is particularly affected by this shift due to its reliance on external investments. While oil projects are the primary focus of these funding restrictions, natural gas projects are also experiencing residual impacts. For instance, over 40 global banks have announced boycotts of investments in the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) linking Uganda and Tanzania. Similarly, the Kudu gas project in Namibia has faced a 13-year delay due to financing challenges, and the U.S. EXIM Bank is reassessing its $4.7 billion commitment to TotalEnergies’ Mozambique LNG project.

Other funding options…

Moneda estimates that $88 billion annual investment is needed over the next five years to cater to domestic needs as well as export opportunities. The African Energy Bank (AEB), promoted by the African Petroleum Producers Organization (APPO) and Afreximbank, aims to provide $5 billion in funding starting January 28, 2025 to this effect. While promising, this represents only a fraction of the required investment. Another untapped resource is Africa’s $700 billion in public pension funds (PPFs), much of which is currently invested abroad. Redirecting these funds toward domestic energy projects could make a significant impact, as demonstrated by countries like Norway and the Netherlands.

However, funding alone is not enough. Investments must be inclusive, reaching all players across the industry hierarchy, from multinational contractors to SMEs.

Leave a Reply