Across the continent, domestic institutional capital held by pension funds, insurance companies, sovereign wealth funds, and development banks exceed $1.1 trillion. According to the Africa Finance Corporation, this pool is expected to grow significantly over the coming decades. Pension funds alone manage roughly $455 billion. Yet only a very small share of this capital flows to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), even though these businesses drive jobs, productivity, and local value creation.

In Nigeria for example, over 60% of pension assets are invested in federal government securities, while less than 1% goes into private equity, and even less into structured private credit. Similar patterns exist across many African countries. Capital is concentrated in instruments designed to preserve value, not in mechanisms designed to grow the real economy.

At the same time, the African diaspora sent approximately $56 billion in remittances in 2024, making it the continent’s largest source of non-debt external funding, surpassing both foreign direct investment and official development assistance. As stated by former African Development Bank President, Dr. Akinwumi Adesina, “The African diaspora has become the largest financier of Africa! And it is not debt; it is 100% gifts or grants”, highlighting the transformative role of remittances as a non-debt funding source. Despite the size of these flows, the majority are directed toward consumption rather than productive investment, leaving it disconnected from productive activities that could drive long-term growth.

Meanwhile, the African Development Bank (AfDB) estimates that Africa’s SME financing gap is a staggering $421 billion, the largest SME financing gap globally. This is not a contradiction, but a clear sign of a systemic failure in capital mobilization.

The Real Problem: Capital Misalignment, Not Shortage

The data tells us that Africa does not lack capital; instead, it lacks the right systems to absorb and deploy capital where it can be most impactful.

Institutional capital, such as pension funds and insurance assets, is long-term in nature, making it well-suited for investments in infrastructure and cash-flow-generating SMEs. Unfortunately, existing financial systems across the continent are poorly equipped to connect these pools of capital with businesses operating in volatile sectors such as agriculture, energy, and infrastructure.

Instead of being directed into the real economy, much of this capital is tied up in low-risk government instruments or invested offshore. This conservative approach to capital allocation protects value in the short term but weakens the broader economy, making it less dynamic and less capable of achieving transformative growth.

The Economic Disconnect

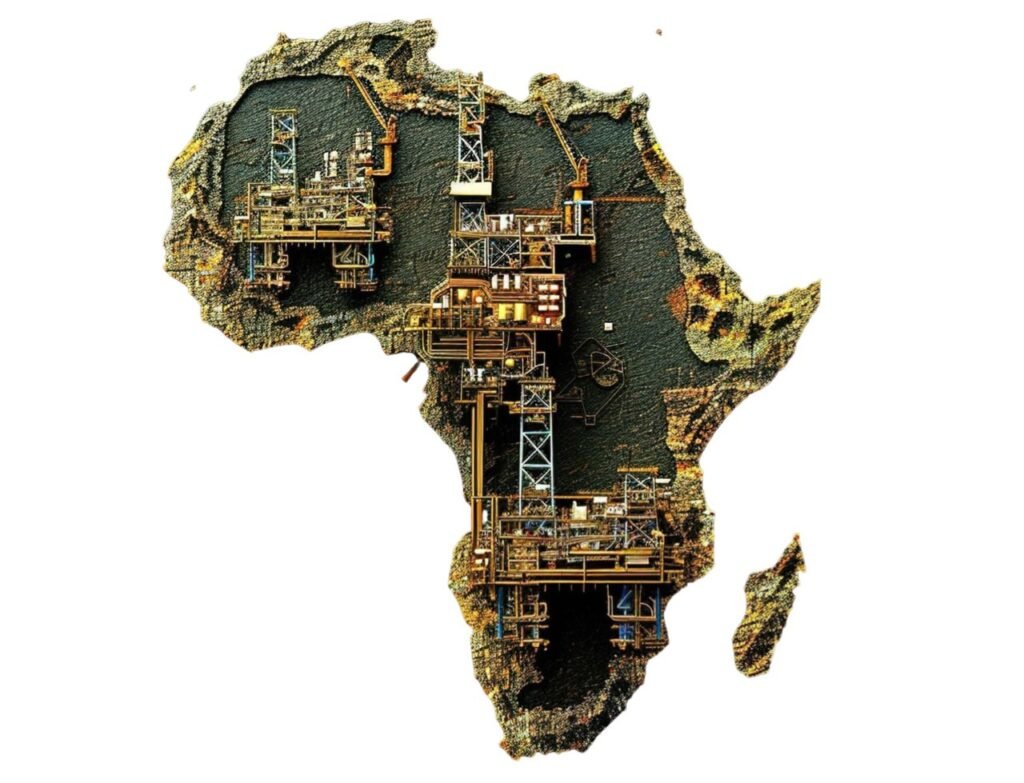

Large-scale anchor projects; such as the Dangote Refinery in Nigeria, LNG developments in Mozambique, or oil and gas discoveries in Namibia and Senegal, are creating unprecedented demand for local suppliers, contractors, logistics providers, and processors. Governments are backing this shift through local content policies, designed to increase domestic participation.

However, many of the SMEs positioned to meet these opportunities are struggling to access the financing they need to scale their operations. Banks prefer collateral-heavy lending and short-term loans that are ill-suited to the needs of businesses with long-term contracts. Equity investments are often too slow and too expensive, while private credit—designed to support businesses with predictable cash flows and signed contracts—remains underdeveloped. As a result, viable SMEs with the capacity to participate in high-value supply chains are left underfunded, while institutional capital continues to sit idle in low-risk assets.

How Private Credit Can Unlock Economic Potential

Private credit is the missing link that can bridge the gap between available capital and the SMEs that are essential for Africa’s economic development. Unlike traditional loans, private credit is based on cash flows and operational performance rather than just collateral, making it better suited to financing businesses in sectors like energy, agriculture, and infrastructure.

Private credit allows capital to follow contracts, not just collateral, aligning repayment schedules with the cash flows of the business. This approach helps absorb volatility by structuring deals in ways that are not punitive but instead reflect the operational realities of the business. By doing so, private credit can offer a solution to the liquidity problems faced by SMEs, providing them with the capital they need to execute contracts, grow, and create jobs.

While the potential of private credit is clear, it remains largely underdeveloped in Africa. Institutional investors in Africa, including pension funds and insurance companies, have yet to fully embrace private credit, which leaves a large portion of available capital sitting unused. This gap exists not because investors are unwilling to take risks, but because there are no robust systems in place to manage those risks effectively.

From Capital Accumulation to Capital Circulation

Moneda Invest Africa’s “Africa Funds Africa” campaign calls for a shift from simply accumulating capital to circulating it within the real economy.

Redirecting even a fraction of Africa’s $1.1 trillion in institutional capital, combined with the $56 billion in diaspora remittances, into execution-backed private credit could close the SME financing gap. This shift would create jobs, strengthen local value chains, and reduce fiscal pressure on governments. It would also deliver long-term returns to investors, creating a virtuous cycle of growth.

Studies suggest that better alignment between capital and economic activity could unlock GDP growth of up to 12% across key African markets, driven largely by the growth of SMEs and infrastructure projects.

Africa’s Economic Transformation: A Choice to Make

Africa’s challenge is no longer about potential. With over $1.1 trillion in institutional capital and $56 billion in remittances, the resources are already in place. The real question is whether African capital will remain misaligned, parked in low-risk instruments or offshore assets, or whether it will be deliberately directed toward sectors that can drive long-term growth.

Moneda’s “Africa Funds Africa” campaign is an invitation to rethink how capital functions in Africa not as a passive store of wealth, but as an active instrument for economic resilience. The future of Africa’s economic transformation will depend on how this vast pool of capital is deployed and what it is structured to build.

By Onyinye Nwafor

Leave a Reply